- DBMS - Home

- DBMS - Overview

- DBMS - Architecture

- DBMS - Data Models

- DBMS - Data Schemas

- DBMS - Data Independence

- DBMS - System Environment

- Centralized and Client/Server Architecture

- DBMS - Classification

- Relational Model

- DBMS - Codd's Rules

- DBMS - Relational Data Model

- DBMS - Relational Model Constraints

- DBMS - Relational Database Schemas

- DBMS - Handling Constraint Violations

- Entity Relationship Model

- DBMS - ER Model Basic Concepts

- DBMS - ER Diagram Representation

- Relationship Types and Relationship Sets

- DBMS - Weak Entity Types

- DBMS - Generalization, Aggregation

- DBMS - Drawing an ER Diagram

- DBMS - Enhanced ER Model

- Subclass, Superclass and Inheritance in EER

- Specialization and Generalization in Extended ER Model

- Data Abstraction and Knowledge Representation

- Relational Algebra

- DBMS - Relational Algebra

- Unary Relational Operation

- Set Theory Operations

- DBMS - Database Joins

- DBMS - Division Operation

- DBMS - ER to Relational Model

- Examples of Query in Relational Algebra

- Relational Calculus

- Tuple Relational Calculus

- Domain Relational Calculus

- Relational Database Design

- DBMS - Functional Dependency

- DBMS - Inference Rules

- DBMS - Minimal Cover

- Equivalence of Functional Dependency

- Finding Attribute Closure and Candidate Keys

- Relational Database Design

- DBMS - Keys

- Super keys and candidate keys

- DBMS - Foreign Key

- Finding Candidate Keys

- Normalization in Database Designing

- Database Normalization

- First Normal Form

- Second Normal Form

- Third Normal Form

- Boyce Codd Normal Form

- Difference Between 4NF and 5NF

- Structured Query Language

- Types of Languages in SQL

- Querying in SQL

- CRUD Operations in SQL

- Aggregation Function in SQL

- Join and Subquery in SQL

- Views in SQL

- Trigger and Schema Modification

- Storage and File Structure

- DBMS - Storage System

- DBMS - File Structure

- DBMS - Secondary Storage Devices

- DBMS - Buffer and Disk Blocks

- DBMS - Placing File Records on Disk

- DBMS - Ordered and Unordered Records

- Indexing and Hashing

- DBMS - Indexing

- DBMS - Single-Level Ordered Indexing

- DBMS - Multi-level Indexing

- Dynamic B- Tree and B+ Tree

- DBMS - Hashing

- Query Processing and Optimization

- Heuristics in Query Processing

- Transaction and Concurrency

- DBMS - Transaction

- DBMS - Scheduling Transactions

- DBMS - Testing Serializability

- DBMS - Conflict Serializability

- DBMS - View Serializability

- DBMS - Concurrency Control

- DBMS - Lock Based Protocol

- DBMS - Timestamping based Protocol

- DBMS - Phantom Read Problem

- DBMS - Dirty Read Problem

- DBMS - Thomas Write Rule

- DBMS - Deadlock

- Backup and Recovery

- DBMS - Data Backup

- DBMS - Data Recovery

- DBMS Useful Resources

- DBMS - Quick Guide

- DBMS - Useful Resources

- DBMS - Discussion

DBMS - View Serializability

View serializability determines if a schedule of transactions maintains database consistency or not. While conflict serializability is commonly used because of its straightforward algorithms, view serializability is a broader concept and covers more schedules. In this chapter, we will explore view serializability in detail, understand its theoretical basics, see examples, and learn a shortcut for checking view serializability.

Schedules in DBMS

Schedules in DBMS refer to the order in which operations from multiple transactions are executed. Scheduling shows how database transactions overlap when processed simultaneously. Schedules play a critical role in determining if the database remains consistent after concurrent execution.

Schedules can be of two types −

- Consistent Schedules − A schedule is consistent if it is executing transactions simultaneously produces the same result as executing them one by one in a serial order. The consistency shows that the database remains correct, no matter how transactions are arranged.

- Inconsistent Schedules − An inconsistent schedule on the other hand makes data incorrect data due to improper execution. This happens when transactions interfere with each other. They are causing errors in the final database state.

The Concept of View Serializability

View serializability is a theoretical method used to determine if a non-serial schedule can be rearranged into a serial schedule or not. If the rearrangement is possible without altering the final result, the schedule to be considered as view serializable.

Conflict serializability is easier to implement. It covers a limited set of consistent schedules. View serializability includes a broader range of schedules, making it more comprehensive. However, checking view serializability can be computationally complex.

Conflict Serializability vs. View Serializability

To differentiate between conflict and view serializability, let us see an everyday analogy of these two concepts.

- Conflict Serializability is like being in a specific part of a city, say "Shyambazar" in Kolkata.

- View Serializability covers the entire city of Kolkata.

- Consistency is like the whole country, India.

If we are in Shyambazar, we are definitely in Kolkata; but being in Kolkata does not mean we are in Shyambazar. Similarly, every conflict serializable schedule is also view serializable. However, not every view serializable schedule is conflict serializable.

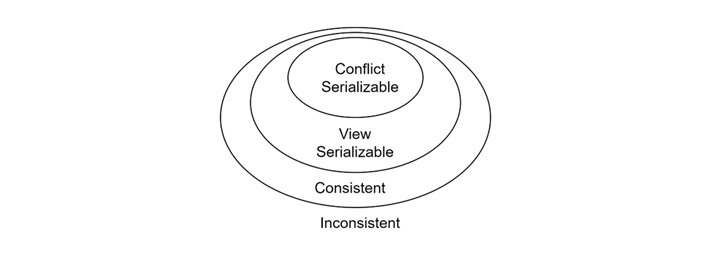

We can express this with the following Venn diagram −

Checking View Serializability

Conflict serializability works by swapping non-conflicting instructions. This is making it easier to apply. However, it cannot identify some consistent schedules. And this is especially those with more complex transaction structures. View serializability addresses this limitation.

The Shortcut Approach

Checking view serializability can be challenging, but there are some shortcut methods. One of such is the checking of Blind Writes.

Blind Writes

The term "blind write" is a case that occurs when a transaction writes a data item without reading its current value. For example −

Write(A) without first doing Read(A).

Blind writes play an important role in determining view serializability.

If the schedule is conflict serializable, it is also view serializable, as it is superset of conflict serializable. No further checks are needed.

Look for Blind Writes − If the schedule is not conflict serializable, check if any transaction performs a blind write.

Final Decision:

- If there are no blind writes, the schedule is not view serializable.

- If there are blind writes, further checks are needed to confirm view serializability.

Why Blind Writes Matter − Blind writes allow transactions to skip reading a data itemâs initial value. This is making them flexible in certain cases. If a schedule includes blind writes, then it has a better chance of being view serializable. This is even when it is not conflict serializable.

Examples of View Serializability

Let us see one examples to understand the process better.

Example 1: Conflict Serializable Schedule

Consider this schedule −

| T1 | T2 |

|---|---|

| Read(A) | |

| Read(B) | |

| Write(A) | |

| Write(B) |

Since T1 and T2 operate on different data items (A and B), there are no conflicts between them. This schedule is conflict serializable and, therefore, also view serializable.

Example 2: Non-Conflict Serializable but View Serializable Schedule

Consider this schedule −

| T1 | T2 |

|---|---|

| Write(A) | |

| Read(A) | |

| Write(A) |

In this case, T1 performs a blind write on A. This writes A without reading its current value. Even though this schedule is not conflict serializable, it may be view serializable because of the blind write.

Example 3: Not View Serializable

Consider this schedule −

| T1 | T2 |

|---|---|

| Read(A) | |

| Read(A) | |

| Write(A) | |

| Write(B) |

Since both transactions read and write the same data item A. And there are no blind writes. This schedule is neither conflict serializable nor view serializable.

Challenges in View Serializability

Checking view serializability is complex. It is considered as NP-Complete Problem, which means it is computationally difficult and time-consuming. Conflict serializability is preferred in practice because of its simpler algorithms. But, understanding view serializability helps build a deeper understanding of how DBMS maintains consistency.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we covered the concept of view Serializability, understood how it relates to conflict serializability, and why it is important in DBMS. We explained how conflict serializable schedules are always view serializable, but not every view serializable schedule is conflict serializable.

We also explored the concept of blind writes and learned a shortcut method for checking if a schedule is view serializable. With the different examples, we saw how transactions behave under different conditions and when a schedule qualifies as view serializable.