- OS - Home

- OS - Overview

- OS - History

- OS - Evolution

- OS - Functions

- OS - Components

- OS - Structure

- OS - Architecture

- OS - Services

- OS - Properties

- Process Management

- Processes in Operating System

- States of a Process

- Process Schedulers

- Process Control Block

- Operations on Processes

- Process Suspension and Process Switching

- Process States and the Machine Cycle

- Inter Process Communication (IPC)

- Remote Procedure Call (RPC)

- Context Switching

- Threads

- Types of Threading

- Multi-threading

- System Calls

- Scheduling Algorithms

- Process Scheduling

- Types of Scheduling

- Scheduling Algorithms Overview

- FCFS Scheduling Algorithm

- SJF Scheduling Algorithm

- Round Robin Scheduling Algorithm

- HRRN Scheduling Algorithm

- Priority Scheduling Algorithm

- Multilevel Queue Scheduling

- Lottery Scheduling Algorithm

- Starvation and Aging

- Turn Around Time & Waiting Time

- Burst Time in SJF Scheduling

- Process Synchronization

- Process Synchronization

- Solutions For Process Synchronization

- Hardware-Based Solution

- Software-Based Solution

- Critical Section Problem

- Critical Section Synchronization

- Mutual Exclusion Synchronization

- Mutual Exclusion Using Interrupt Disabling

- Peterson's Algorithm

- Dekker's Algorithm

- Bakery Algorithm

- Semaphores

- Binary Semaphores

- Counting Semaphores

- Mutex

- Turn Variable

- Bounded Buffer Problem

- Reader Writer Locks

- Test and Set Lock

- Monitors

- Sleep and Wake

- Race Condition

- Classical Synchronization Problems

- Dining Philosophers Problem

- Producer Consumer Problem

- Sleeping Barber Problem

- Reader Writer Problem

- OS Deadlock

- Introduction to Deadlock

- Conditions for Deadlock

- Deadlock Handling

- Deadlock Prevention

- Deadlock Avoidance (Banker's Algorithm)

- Deadlock Detection and Recovery

- Deadlock Ignorance

- Resource Allocation Graph

- Livelock

- Memory Management

- Memory Management

- Logical and Physical Address

- Contiguous Memory Allocation

- Non-Contiguous Memory Allocation

- First Fit Algorithm

- Next Fit Algorithm

- Best Fit Algorithm

- Worst Fit Algorithm

- Buffering

- Fragmentation

- Compaction

- Virtual Memory

- Segmentation

- Paged Segmentation & Segmented Paging

- Buddy System

- Slab Allocation

- Overlays

- Free Space Management

- Locality of Reference

- Paging and Page Replacement

- Paging

- Demand Paging

- Page Table

- Page Replacement Algorithms

- Second Chance Page Replacement

- Optimal Page Replacement Algorithm

- Belady's Anomaly

- Thrashing

- Storage and File Management

- File Systems

- File Attributes

- Structures of Directory

- Linked Index Allocation

- Indexed Allocation

- Disk Scheduling Algorithms

- FCFS Disk Scheduling

- SSTF Disk Scheduling

- SCAN Disk Scheduling

- LOOK Disk Scheduling

- I/O Systems

- I/O Hardware

- I/O Software

- I/O Programmed

- I/O Interrupt-Initiated

- Direct Memory Access

- OS Types

- OS - Types

- OS - Batch Processing

- OS - Multiprogramming

- OS - Multitasking

- OS - Multiprocessing

- OS - Distributed

- OS - Real-Time

- OS - Single User

- OS - Monolithic

- OS - Embedded

- Popular Operating Systems

- OS - Hybrid

- OS - Zephyr

- OS - Nix

- OS - Linux

- OS - Blackberry

- OS - Garuda

- OS - Tails

- OS - Clustered

- OS - Haiku

- OS - AIX

- OS - Solus

- OS - Tizen

- OS - Bharat

- OS - Fire

- OS - Bliss

- OS - VxWorks

- Miscellaneous Topics

- OS - Security

- OS Questions Answers

- OS - Questions Answers

- OS Useful Resources

- OS - Quick Guide

- OS - Useful Resources

- OS - Discussion

Operating System - Segmentation

Segmentation is a memory management technique used in non-contiguous memory allocation systems. This chapter will explain segmentation, how it works, and its implementation in operating systems.

- What is Segmentation?

- Features of Segmentation

- How Segmentation Works?

- The Segment Table

- Paging vs Segmentation

- Pros and Cons of Segmentation

What is Segmentation?

Segmentation is a memory management technique that divides a program's memory into different segments based on the logical divisions of the program. Each segment is used to store a specific part of the program, such as functions, code, or variables. This is different from paging, where memory is divided into fixed-size blocks. Here, the segments match the user's logical view of a program (functions, arrays, modules) to physical memory.

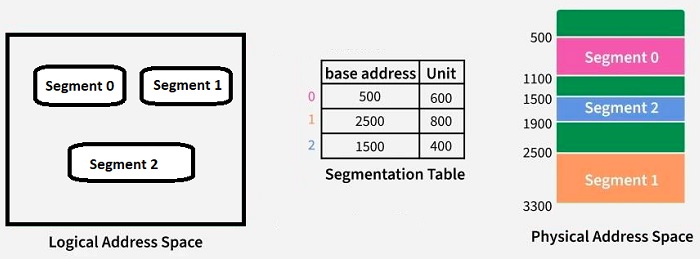

The image below shows how segmentation works in an operating system −

In the image, there are three segments - Segment 0, Segment 1, and Segment 2 in logical memory. Each segment has a base address and unit size in physical memory, these values are stored in the segment table. When a program accesses a memory location, the operating system uses the segment table to translate the logical address into a physical address.

For example, the base address of Segment 0 is 500, and the unit size is 600. So the physical address for logical address (0, 600) will be calculated as −

Physical Address = Base Address + Offset

= 500 + 600

= 1100

Hence, The logical address (500, 1100) is given to segment 0 in physical memory.

Features of Segmentation

Here are some key features related to segmentation −

- Variable sized segments: Each segment can have a different size based on the program's requirements. Each segments represent meaningful units like code, stack, data, or modules.

- Logical Addressing: In segmentation, a logical address is represented as a tuple (segment number, offset) where the segment number identifies the segment and the offset specifies the location within that segment.

- Segment Table: The operating system maintains a segment table that maps segment numbers to physical memory addresses. Each entry in the segment table contains the base address and limit (size) of the segment.

- Protection and Sharing: Different segments can have access rights (read, write, execute) and can be shared among processes.

- Fragmentation: Segmentation can lead to external fragmentation, because of loading and unloading of segments of variable sizes. But it does not suffer from internal fragmentation since segments are not fixed in size.

How Segmentation Works?

- Before a program is loaded into memory, the operating system divides it into segments based on its logical structure. For example, a program may be divided into code segment, data segment, stack segment, etc.

- When a program is executed, the operating system allocates memory for each segment in the physical memory (RAM) based on the size of the segment.

- The operating system keeps a data structure called the segment table that maps each segment number to its corresponding base address and limit in physical memory.

- When a program accesses a memory location, it provides a logical address consisting of a segment number and an offset. The operating system uses the segment table to translate the logical address into a physical address by adding the base address of the segment to the offset.

- If the offset exceeds the limit of the segment, then a segmentation fault occurs. This will prevent the program from accessing memory outside its allocated segment.

The Segment Table

The segment table is a data structure used by the operating system to keep track of the segments allocated to a process. It maps two-dimensional logical addresses into one-dimensional physical addresses. Each entry in the segment table contains the following information −

- Segment Number − A unique identifier for each segment.

- Base Address − The starting physical address of the segment in memory.

- Limit − The size of the segment, which defines the maximum offset that can be accessed within the segment.

Example

Here is an example of a segment table −

| Segment Number | Base Address | Limit |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1000 | 500 |

| 1 | 2000 | 300 |

| 2 | 3000 | 400 |

Paging vs Segmentation

Here is a comparison between paging and segmentation −

| Feature | Paging | Segmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Memory management technique that divides memory into fixed-size pages that are mapped to physical frames. | Memory management technique that divides memory into variable-size segments based on the logical divisions of a program. |

| Division of Memory | Fixed-size pages | Variable-size segments |

| Addressing | One-dimensional (page number, offset) | Two-dimensional (segment number, offset) |

| Fragmentation | Likely to suffer from internal fragmentation | May suffer from external fragmentation |

| Logical Structure | No relation to logical structure of program | Matches logical structure of program, i.e., functions, modules etc |

| Protection and Sharing | Less protection and sharing capabilities | Better protection and sharing capabilities |

Pros and Cons of Segmentation

The segmentation technique following advantages −

- Logical Organization − Segmentation allows programs to be divided into logical units. This makes it easier to manage and understand the program structure.

- Protection and Sharing − Sometimes in programs, different segments can have different access rights. Segmentation can ensure this by various segments having different protection levels.

- Dynamic Growth − Segments can grow or shrink dynamically as needed. This is useful for data structures like stacks and heaps.

However, segmentation also comes with following drawbacks −

- External Fragmentation − When segments are loaded and unloaded from memory for long time, the memory blocks become fragmented. This can leads to wastage of memory.

- Complexity − The management of variable-sized segments can be more complex than fixed-size pages, leading to increased overhead in the memory management system.

- Size Limitations − Each segment has a size limit, which may restrict the amount of memory that can be allocated to a particular segment.

Conclusion

Segmentation is a memory allocation technique that divides a program's memory into different segments based on its logical structure. This is different from paging, which divides memory into fixed-size pages. The main aim of segmentation is to provide a more logical view of memory to the user and to facilitate protection and sharing of memory segments. However, segmentation can lead to external fragmentation and increased complexity in memory management.