- Distributed Database Environments

- DDBMS - Design Strategies

- DDBMS - Distribution Transparency

- DDBMS - Database Control

- Query Optimization

- Relational Algebra Query

- Query Optimization Centralized

- Query Optimization in Distributed

- Concurrency Control

- Transaction Processing Systems

- DDBMS - Controlling Concurrency

- DDBMS - Deadlock Handling

- Failure and Recovery

- DDBMS - Replication Control

- DDBMS - Failure & Commit

- DDBMS - Database Recovery

- Distributed Commit Protocols

- Distributed DBMS Security

- Database Security & Cryptography

- Security in Distributed Databases

- Distributed DBMS Resources

- DDBMS - Quick Guide

- DDBMS - Useful Resources

- DDBMS - Discussion

DDBMS - Transaction Processing Systems

This chapter discusses the various aspects of transaction processing. Well also study the low level tasks included in a transaction, the transaction states and properties of a transaction. In the last portion, we will look over schedules and serializability of schedules.

Transactions

A transaction is a program including a collection of database operations, executed as a logical unit of data processing. The operations performed in a transaction include one or more of database operations like insert, delete, update or retrieve data. It is an atomic process that is either performed into completion entirely or is not performed at all. A transaction involving only data retrieval without any data update is called read-only transaction.

Each high level operation can be divided into a number of low level tasks or operations. For example, a data update operation can be divided into three tasks −

read_item() − reads data item from storage to main memory.

modify_item() − change value of item in the main memory.

write_item() − write the modified value from main memory to storage.

Database access is restricted to read_item() and write_item() operations. Likewise, for all transactions, read and write forms the basic database operations.

Transaction Operations

The low level operations performed in a transaction are −

begin_transaction − A marker that specifies start of transaction execution.

read_item or write_item − Database operations that may be interleaved with main memory operations as a part of transaction.

end_transaction − A marker that specifies end of transaction.

commit − A signal to specify that the transaction has been successfully completed in its entirety and will not be undone.

rollback − A signal to specify that the transaction has been unsuccessful and so all temporary changes in the database are undone. A committed transaction cannot be rolled back.

Transaction States

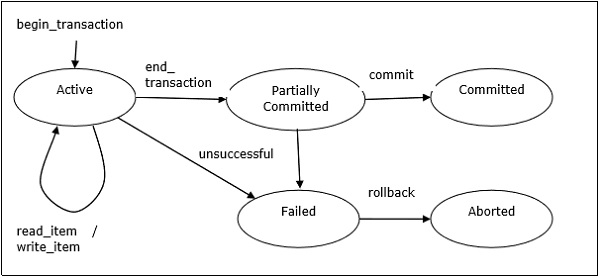

A transaction may go through a subset of five states, active, partially committed, committed, failed and aborted.

Active − The initial state where the transaction enters is the active state. The transaction remains in this state while it is executing read, write or other operations.

Partially Committed − The transaction enters this state after the last statement of the transaction has been executed.

Committed − The transaction enters this state after successful completion of the transaction and system checks have issued commit signal.

Failed − The transaction goes from partially committed state or active state to failed state when it is discovered that normal execution can no longer proceed or system checks fail.

Aborted − This is the state after the transaction has been rolled back after failure and the database has been restored to its state that was before the transaction began.

The following state transition diagram depicts the states in the transaction and the low level transaction operations that causes change in states.

Desirable Properties of Transactions

Any transaction must maintain the ACID properties, viz. Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability.

Atomicity − This property states that a transaction is an atomic unit of processing, that is, either it is performed in its entirety or not performed at all. No partial update should exist.

Consistency − A transaction should take the database from one consistent state to another consistent state. It should not adversely affect any data item in the database.

Isolation − A transaction should be executed as if it is the only one in the system. There should not be any interference from the other concurrent transactions that are simultaneously running.

Durability − If a committed transaction brings about a change, that change should be durable in the database and not lost in case of any failure.

Schedules and Conflicts

In a system with a number of simultaneous transactions, a schedule is the total order of execution of operations. Given a schedule S comprising of n transactions, say T1, T2, T3..Tn; for any transaction Ti, the operations in Ti must execute as laid down in the schedule S.

Types of Schedules

There are two types of schedules −

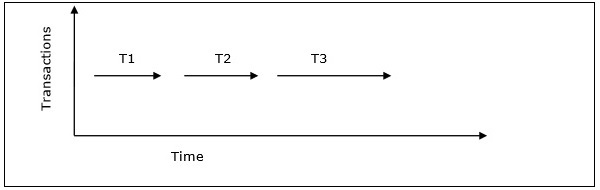

Serial Schedules − In a serial schedule, at any point of time, only one transaction is active, i.e. there is no overlapping of transactions. This is depicted in the following graph −

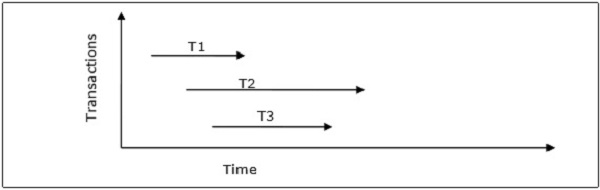

Parallel Schedules − In parallel schedules, more than one transactions are active simultaneously, i.e. the transactions contain operations that overlap at time. This is depicted in the following graph −

Conflicts in Schedules

In a schedule comprising of multiple transactions, a conflict occurs when two active transactions perform non-compatible operations. Two operations are said to be in conflict, when all of the following three conditions exists simultaneously −

The two operations are parts of different transactions.

Both the operations access the same data item.

At least one of the operations is a write_item() operation, i.e. it tries to modify the data item.

Serializability

A serializable schedule of n transactions is a parallel schedule which is equivalent to a serial schedule comprising of the same n transactions. A serializable schedule contains the correctness of serial schedule while ascertaining better CPU utilization of parallel schedule.

Equivalence of Schedules

Equivalence of two schedules can be of the following types −

Result equivalence − Two schedules producing identical results are said to be result equivalent.

View equivalence − Two schedules that perform similar action in a similar manner are said to be view equivalent.

Conflict equivalence − Two schedules are said to be conflict equivalent if both contain the same set of transactions and has the same order of conflicting pairs of operations.