- Modern Indian History - Home

- Decline of Mughal Empire

- Bahadur Shah I

- Jahandar Shah

- Farrukh Siyar

- Muhammad Shah

- Nadir Shah’s Outbreak

- Ahmed Shah Abdali

- Causes of Decline of Mughal Empire

- South Indian States in 18th Century

- North Indian States in 18th Century

- Maratha Power

- Economic Conditions in 18th Century

- Social Conditions in 18th Century

- Status of Women

- Arts and Paintings

- Social Life

- The Beginnings of European Trade

- The Portuguese

- The Dutch

- The English

- East India Company (1600-1744)

- Internal Organization of Company

- Anglo-French Struggle in South India

- The British Conquest of India

- Mysore Conquest

- Lord Wellesley (1798-1805)

- Lord Hastings

- Consolidation of British Power

- Lord Dalhousie (1848-1856)

- British Administrative Policy

- British Economic Policies

- Transport and Communication

- Land Revenue Policy

- Administrative Structure

- Judicial Organization

- Social and cultural Policy

- Social and Cultural Awakening

- The Revolt of 1857

- Major Causes of 1857 Revolt

- Diffusion of 1857 Revolt

- Centers of 1857 Revolt

- Outcome of 1857 Revolt

- Criticism of 1857 Revolt

- Administrative Changes After 1858

- Provincial Administration

- Local Bodies

- Change in Army

- Public Service

- Relations with Princely States

- Administrative Policies

- Extreme Backward Social Services

- India & Her Neighbors

- Relation with Nepal

- Relation with Burma

- Relation with Afghanistan

- Relation with Tibet

- Relation with Sikkim

- Relation with Bhutan

- Economic Impact of British Rule

- Nationalist Movement (1858-1905)

- Predecessors of INC

- Indian National Congress

- INC & Reforms

- Religious & Social Reforms

- Religious Reformers

- Women’s Emancipation

- Struggle Against Caste

- Nationalist Movement (1905-1918)

- Partition of Bengal

- Indian National Congress (1905-1914)

- Muslim & Growth Communalism

- Home Rule Leagues

- Struggle for Swaraj

- Gandhi Assumes Leadership

- Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre

- Khilafat & Non-Cooperation

- Second Non-Cooperation Movement

- Civil Disobedience Movement II

- Government of India Act (1935)

- Growth of Socialist Ideas

- National Movement World War II

- Post-War Struggle

- Clement Attlee’s Declaration

- Reference & Disclaimer

Administrative Structure

In the beginning, the Company left the administration of its possessions in India in Indian hands, confining its activities to supervision. But soon found `that British aims were not adequately served by following old methods of administration. Consequently, the Company took all aspects of administration in its own hand.

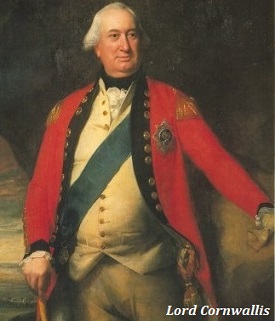

Under Warren Hastings and Cornwallis, the administration of Bengal was completely overhauled and found a new system based on the English pattern.

The spread of British power to new areas, new problems, new needs, new experiences, and new ideas led to changes in the system of administration. But the overall objectives of imperialism were never forgotten.

Strength of British Administrative System

-

The British administration in India was based on three pillars −

The Civil Service,

The Army, and

The Police.

The chief aim of British-Indian administration was the maintenance of law and order and the perpetuation of British rule. Without law and order, British merchants and British manufacturers could not hope to sell their goods in every nook and corner of India.

The British, being foreigners, could not hope to win the affections of the Indian people; they, therefore, relied on superior force rather than on public support for the maintenance of their control over India.

Civil Service

The Civil Service was brought into existence by Lord Cornwallis.

The East India Company had from the beginning carried on its trade in the East through servants who were paid low wages but who were permitted to trade privately.

-

Later, when the Company became a territorial power, the same servants assumed administrative functions. They now became extremely corrupt by −

Oppressing local weavers and artisans, merchants, and zamindars,

Extorting bribes and 'gifts' from rajas and nawabs, and

Indulging in illegal private trade. They amassed untold wealth with which they retired to England.

Clive and Warren Hastings made attempts to put an end to their corruption, but were only partially successful.

Cornwallis, who came to India as Governor-General in 1786, was determined to purify the administration, but he realized that the Company's servants would not give honest and efficient service so long as they were not given adequate salaries.

Cornwallis, therefore, enforced the rules against private trade and acceptance of presents and bribes by officials with strictness. At the same time, he raised the salaries of the Company's servants. For example, the Collector of a district was to be paid Rs 1,500 a month and one per cent commission on the revenue collection of his district.

Cornwallis also laid down that promotion in the Civil Service would be by seniority so that its members would remain independent of outside influence.

In 1800, Lord Wellesley pointed out that even though civil servants often ruled over vast areas, they came to India at the immature age of 18 or so and were given no regular training before starting on their jobs. They generally lacked knowledge of Indian languages.

Wellesley, therefore, established the College of Fort William at Calcutta for the education of young recruits to the Civil Service.

The Directors of the Company disapproved of his action and in 1806 replaced it by their own East Indian College at Haileybury in England.

Till 1853, all appointments to the Civil Service were made by the Directors of the East India Company who placated the members of the Board of Control by letting them make some of the nominations.

The Directors fought hard to retain this lucrative and prized privilege and refused to surrender it even when their other economic and political privileges were taken away by Parliament.

The Directors lost it finally in 1853 when the Charter Act decreed that all recruits to the Civil Service were to be selected through a competitive examination.

A special feature of the Indian Civil Service since the days of Cornwallis was the rigid and complete exclusion of Indians (from it).

It was laid down officially in 1793 that all the higher posts in administration worth more than £ 500 a year in salary were to be held by Englishmen. This policy was also applied to other branches of Government, such as the army, police, judiciary, and engineering.

The Indian Civil Service gradually developed as one of the most efficient and powerful civil services in the world.

Its members exercised vast power and often participated in the making of policy. They developed certain traditions of independence, integrity, and hard work, though these qualities obviously served British and not Indian interests.

Satyendranath Tagore was the first Indian who passed the Indian Civil Service examination in 1863 and hold 4th Rank. He was an author, linguist, song composer. He made significant contribution towards the emancipation of women in Indian society during the British Rule.

Army

-

The army of the British regime in India was fulfilled three important functions −

It was the instrument through which the Indian powers were conquered;

It defended the British Empire in India from foreign rivals; and

It safeguarded British supremacy from the ever-present threat of internal revolt.

The bulk of the Company's army consisted of Indian soldiers, recruited chiefly from the area at present included in U.P. and Bihar.

For instance, in 1857, the strength of the army in India was 311,400 of whom 265,903 were Indians. Its officers were, however, exclusively British, at least since the days of Cornwallis.

In 1856, only three Indians in the army received a salary of Rs. 300 per month and the highest Indian officer was a subedar.

A large number of Indian troops had to be employed as the British troops were too expensive. Moreover, the population of Britain was perhaps too small to provide the large number of soldiers needed for the conquest of India.

As a counterweight, the army was officered entirely by British officials and a certain number of British troops were maintained to keep the Indian soldiers under control.

Police

Cornwallis had created the police system, which was one of the most popular strengths for the British rule.

Cornwallis relieved the zamindars of their police functions and established a regular police force to maintain law and order.

Interestingly, this put India ahead of Britain where a system of police had not developed yet.

Cornwallis established a system of circles or thanas headed by a daroga, who was an Indian. Later, the post of the District Superintendent of Police was mated to head the police organization in a district.

Once again, Indians were excluded from all superior posts. In the villages the duties of the police continued to he performed by village-watchmen who were maintained by the villagers.

The police gradually succeeded in reducing major crimes such as dacoity.

One of its major achievements was the suppression of thugs who robbed and killed travelers on the highways, particularly in Central India.

The police also prevented the organization of a large-scale conspiracy against foreign control, and when the national movement arose, the police were used to suppress it.